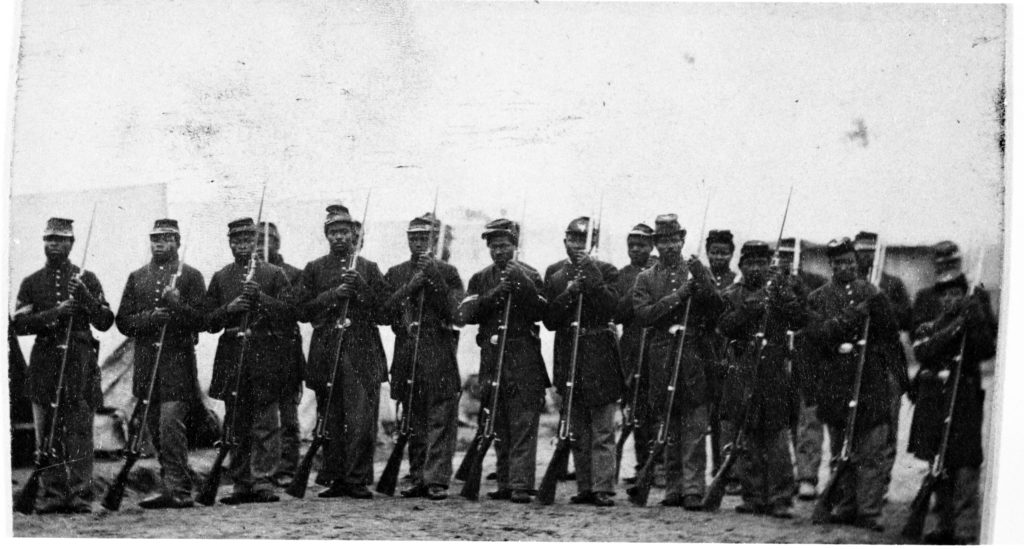

United States Colored Troops, Port Hudson, LA, c. 1864. Collection of the National Archives, public domain.

“Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.” —Frederick Douglass

Of the approximately 180,000 African American men who served in the United States Colored Troops during the American Civil War, 8,612 came from Pennsylvania—the largest contingent from any Northern state. Additional men from the commonwealth served with the United States Navy. At the height of the conflict, African American soldiers made up 10% of the Union Army and 23% of all enlisted men on U.S. naval vessels.

African Americans regularly served in the United States Navy and the merchant marine before the Civil War, perhaps accounting for one-fifth of the nation’s sailors in the early nineteenth century. Prior to the war, the United States Navy capped the percentage of African American sailors to 5% of its enlisted ranks, but to meet its manpower needs it recruited more Black sailors starting in 1861. Throughout the war, African American average 16% of the navy’s personnel and received the same pay as white sailors. Furthermore, the nature of naval life meant that segregation was not possible on naval vessels. However, Black sailors were typically rated as “landsmen” rather than “sailors” when they enlisted, and often limited to jobs as stewards, cooks, or musicians.

Black crew members on the USS Miami sewing and relaxing on the forecastle, starboard side, circa 1864–65. This image is a detail from the right side of Naval History and Heritage Command photo NH 60873 (NH 55510).

The Union Army initially excluded African American men from federal military service (though Kansas, South Carolina and Louisiana did form Black regiments prior to 1863). President Lincoln officially authorized the use of African American troops for United States Army with the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863:

“And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.”

After January 1, 1863, states such as Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island created segregated units for African American servicemen and even recruited men from Pennsylvania to serve in them. However, Pennsylvania’s governor Andrew Curtain refused to authorize Black regiments from the state.

The Union Army’s desperate need for troops led the War Department to issue General Order No. 143 on May 22, 1863, creating the Bureau of Colored Troops. Rather than relying on the states to create segregated units, the government created its own federal regiments: the United States Colored Troops.

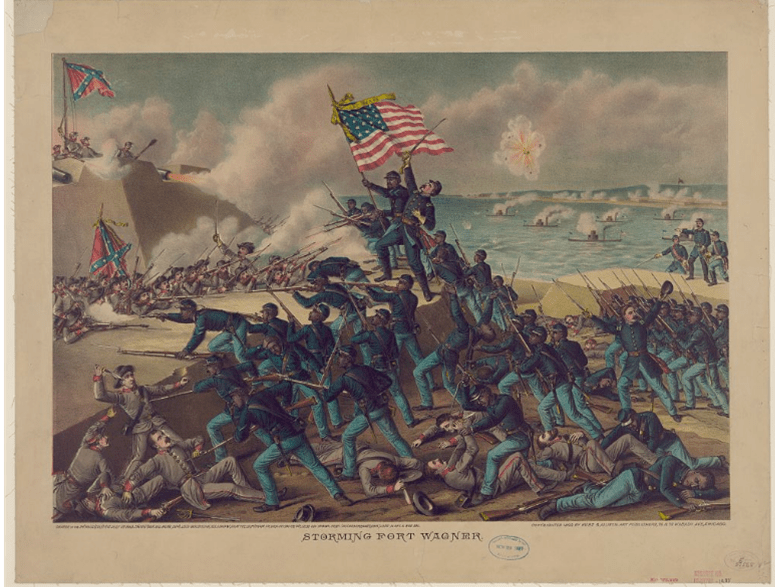

At first, African Americans were hesitant to enlist in the United States Colored Troops. However, following the courage under fire demonstrated by the 54th and 55th Massachusetts regiments at the Battle of Fort Wagner in Charleston Harbor on July 18, 1863, the ranks of the USCT began to fill.

Storming of Fort Wagner. Lithography by Kurz and Allison. Library of Congress.

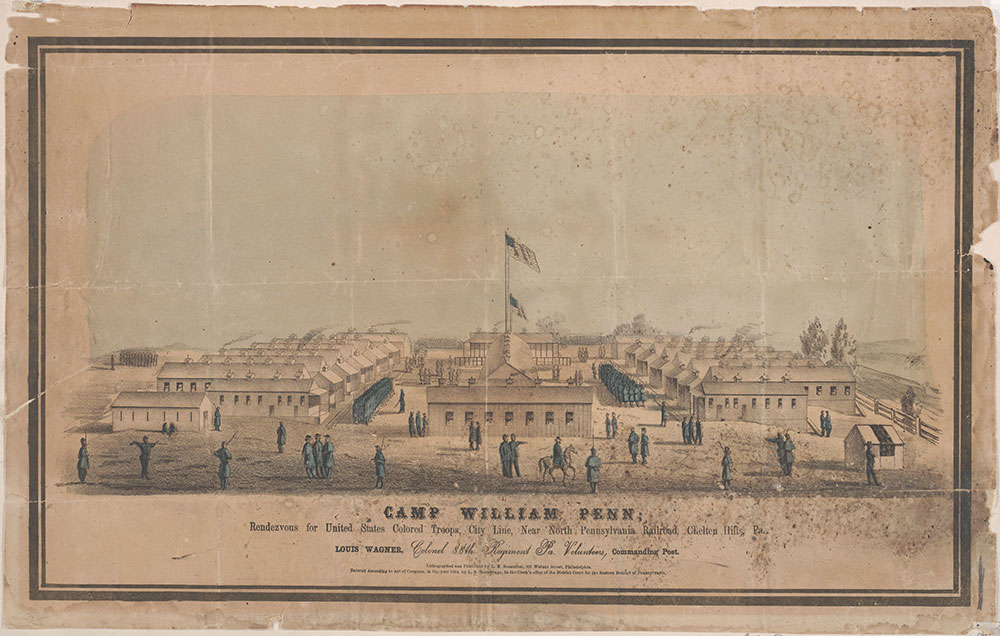

Camp William Penn outside Philadelphia in La Mott (Cheltenham, PA), became an important training ground for African American men who entered service from Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey. All told, more than 11,000 African American Civil War soldiers would be organized, trained, and mustered into serve on the grounds of Camp William Penn.

In the critical last years of the war, the United States Colored Troops gave the Union Army a vital influx of energy and manpower that contributed to the ultimate defeat of the Confederate Army. While racism limited the use of Black Troops in combat, African American soldiers fought bravely in almost every major campaign of the last two years of the Civil War.

African American soldiers filled vital roles throughout the U.S. army. According to the National Archives, “Black soldiers served in artillery and infantry and performed all noncombat support functions that sustain an army, as well. Black carpenters, chaplains, cooks, guards, laborers, nurses, scouts, spies, steamboat pilots, surgeons, and teamsters also contributed to the war cause. There were nearly 80 black commissioned officers. Black women, who could not formally join the Army, nonetheless served as nurses, spies, and scouts.”

While bravely serving their country, these African American soldiers faced hardship and discrimination. African American soldiers would not lead the USCT. Instead, all USCT regiments were commanded by white commissioned officers supported by Black non-commissioned officers. Additionally, the Militia Act of 1862 set pay for Black soldiers at $10 a month, and deducted $3 for their uniform. White soldiers received $13 a month and did not have any payment deducted for clothing. That policy remained in effect until June 1864.

Camp William Penn Lithography by Max Rosenthal. Free Library of Philadelphia.

Additionally, in 1863 the Confederate Congress threatened to enslave any African American soldier captured as a prisoner of war. The abuse of USCT soldiers at Confederate hands included the bloody massacre of USCT soldiers who surrendered following the battle of Fort Pillow on April 12, 1864. The Confederate troops proceeded to massacred 200 members of the United States Colored Troops rather than recognizing them as legitimate prisoners of war. For members of the USCT, putting on the blue uniform carried extraordinary risks.

Approximately 40,000 members of the United States Colored Troops died in service—more than one in five who enlisted. Of those who perished, 75% died from infection or disease.

Those who survived often returned home with injuries or illness contracted during their service. Others suffered from the effects of malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies that they experienced when they were sent to guard the Texas-Mexican border in the summer and fall of 1865 after the war had ended and most white troops returned home.

After the war, the veterans of the United States Colored Troops who survived the war returned to Pennsylvania, joined by many more veterans from Southern states who relocated to Pennsylvania seeking jobs and opportunity. They contributed richly to the prosperity of Pennsylvania’s postwar communities.

Yet even after serving their country, the veterans of the United States Colored Troops often faced injustice and discrimination in life as de facto segregation limited their access to jobs, services, property, and education. Even in death, they were often laid to rest in segregated cemeteries.

Our nation and our states owe an enormous debt of gratitude to these brave men who were willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for their country and to end the evil of slavery. Some died in poverty and were laid to rest in unmarked graves; others received polished marble tombstones provided by the state or federal government that have since toppled or become lost in brush and weeds due to decades of neglect. All deserve final resting places befitting their status as military veterans and in gratitude for their service to the nation.

It falls to us to honor their lives and service by ensuring that the hallowed grounds where these veterans lay are places that reflect the honor and respect that they have earned and so fully deserve.

Resources to Learn More About Pennsylvania USCT and Black Sailors:

Websites:

Camp William Penn Website: “United States Colored Troops: Camp William Penn Headquarters”: https://www.usct.org/

African American Civil War Museum: United States Colored Troops: https://www.afroamcivilwar.org/usct

National Park Service, “The Civil War’s Black Soldiers,” : https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/civil_war_series/2/sec10.htm.

National Park Service, “Soldiers and Sailors Database,” https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm

Naval History and Heritage Command, “African Americans in the U.S. Navy During the Civil War,” https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/civil-war-archive1/african-americans-in-the-u-s–navy-during-the-civil-war.html

American Battlefield Trust, “The Role of African Americans in the United States Army”: https://www.battlefields.org/learn/topics/united-states-colored-troops

National Archives, “Black Soldiers in the U.S. Military During the Civil War”: https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/blacks-civil-war

National Archives, “Black Men in Navy Blue During the Civil War,” by Joseph P. Reidy, https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2001/fall/black-sailors-1.html.

Books:

Ira Berlin, Joseph Reidy, and Leslie Rowland, eds., Freedom’s Soldiers: The Black Military Experience in the Civil War (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Holly A. Pinheiro, The Families’ Civil War: Black Soldiers and the Fight for Racial Justice (University of Georgia Press, 2022).

Donald Scott, Camp William Penn, 1862-1865: America’s First Federal African American Fight for Freedom (Shiffer, 2012).

John Smith, Black Soldiers in Blue: African American Troops in the Civil War Era (University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

Edward McLaughin has also authored and self-published several books on Camp William Penn and African American soldiers’ and sailors’ graves at the Philadelphia National Cemetery:

-

The Camp William Penn Researcher: Newspaper Accounts – Camp William Penn and the Eleven Regiments That Trained There (2022)

-

The Cemetery Monument Hidden in Plain View: A Study of Black Civil War Soldiers & Sailors Buried at the Philadelphia National Cemetery (2021)

-

Where Have All of the Soldiers Gone: Join the Scavenger Hunt for Burial Sites of Camp William Penn Civil War Soldiers (2021)

-

Slaves and Soldiers in the Cemetery: The Philadelphia National Cemetery has a Number of Slaves Who Became Soldiers that were Buried There (2021)

-

The Cemetery Monument Hidden in Plain View A SUPPLEMENT: A Study of Black Civil War Soldiers & Sailors Buried at the Philadelphia National Cemetery (2021)